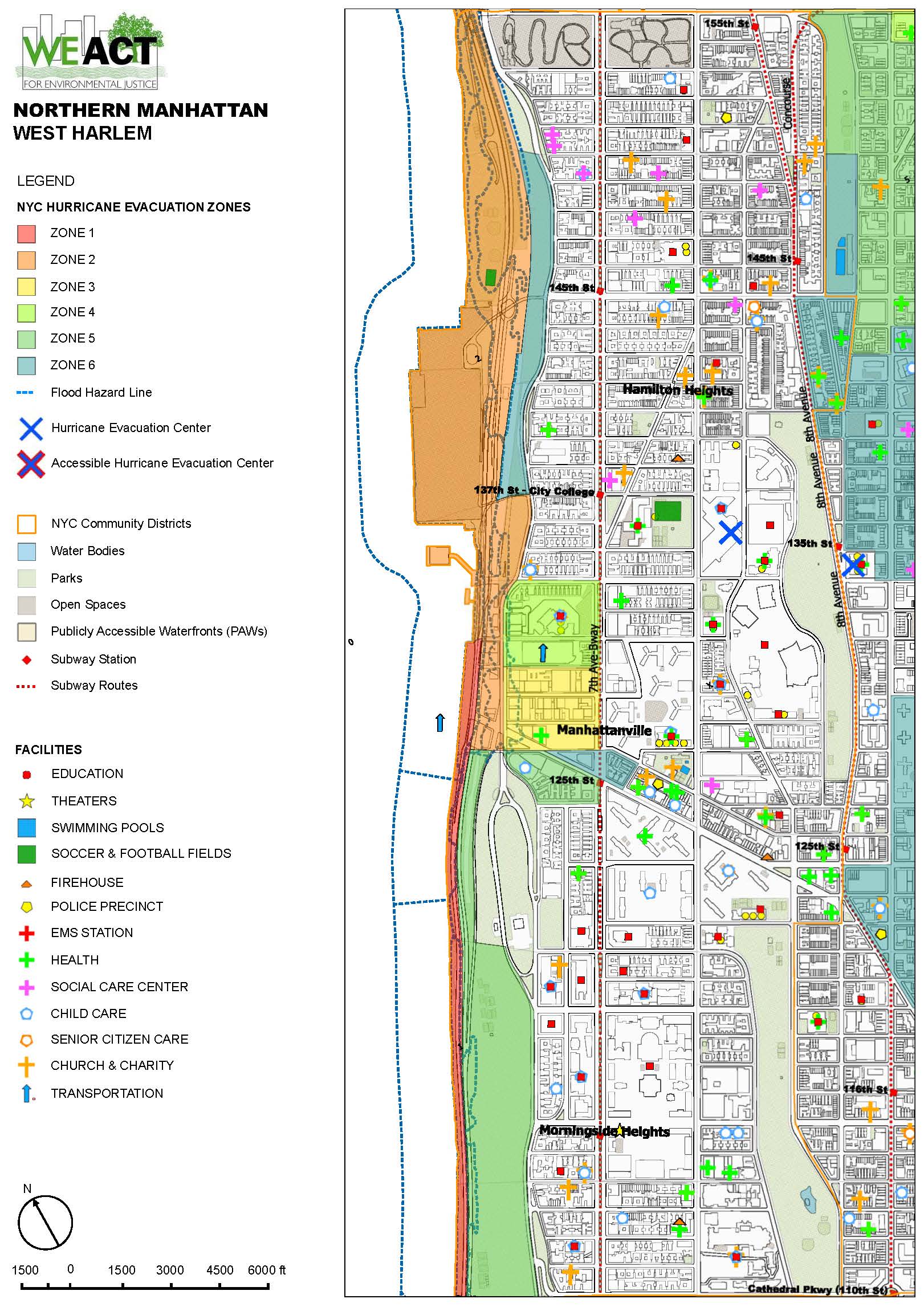

One of WE ACT’s recent ongoing projects is the Northern Manhattan Climate Action Plan, which is focused on developing a community response to the climate change issue facing already precarious populations. The attached map is a community assessment of educational, environmental, and social assets.

One of WE ACT’s recent ongoing projects is the Northern Manhattan Climate Action Plan, which is focused on developing a community response to the climate change issue facing already precarious populations. The attached map is a community assessment of educational, environmental, and social assets.

In the historically redlined neighborhoods of the South Bronx and Northern Manhattan, continual economic disinvestment and environmental abuse has exposed communities to pollution, poor air quality, and climate vulnerability. Planners like Robert Moses who shaped New York City’s development for decades, chose to place destructive and unhealthy construction such as power plants, highways, and waste processing facilities in projects in those neighborhoods. One example is the Cross Bronx Expressway, built in 1948, displacing residents and bisecting an area spanning 113 avenues and boulevards. Another well-known example of this is Hunts Point in the Bronx, which is one of the major repositories for waste and pollution in New York City containing car repair warehouses, dump truck garages, junkyards and a sludge processing plant. Poor air quality is only exacerbated by thousands of trucks which travel into the neighborhood daily to access the community’s fish, produce, and meat markets. In neighborhoods such as Hunts Point and Longwood with immense industry and highway concentrations, pediatric asthma emergency visits are more than double the citywide average.

In the 1980s, community groups rose up to challenge the municipal and federal policies that drove industries, utilities, and landfills into underserved communities. One such group, WE ACT for Environmental Justice, was founded in 1988 after the North River Sewage Treatment Plant, originally slated to be built on the Upper West Side, was relocated to West 135th Street.

The facility had open sewage tanks that gave off an unbearable stench, forcing residents to keep their windows closed even in the summer months. Emissions from the facility’s smokestacks were not up to code either, adding further air pollution to the neighborhood. On MLK Day in 1988, seven protesters, the “Sewage Seven,” blocked traffic on the West Side Highway during rush hour. They eventually sued the City over the sewage plant, winning a settlement for an environmental health fund that led to the creation of West Harlem Environmental Action (known today as WE ACT), by Peggy Shepard, Vernice Miller-Travis (BC ’80), and the late Chuck Sutton.

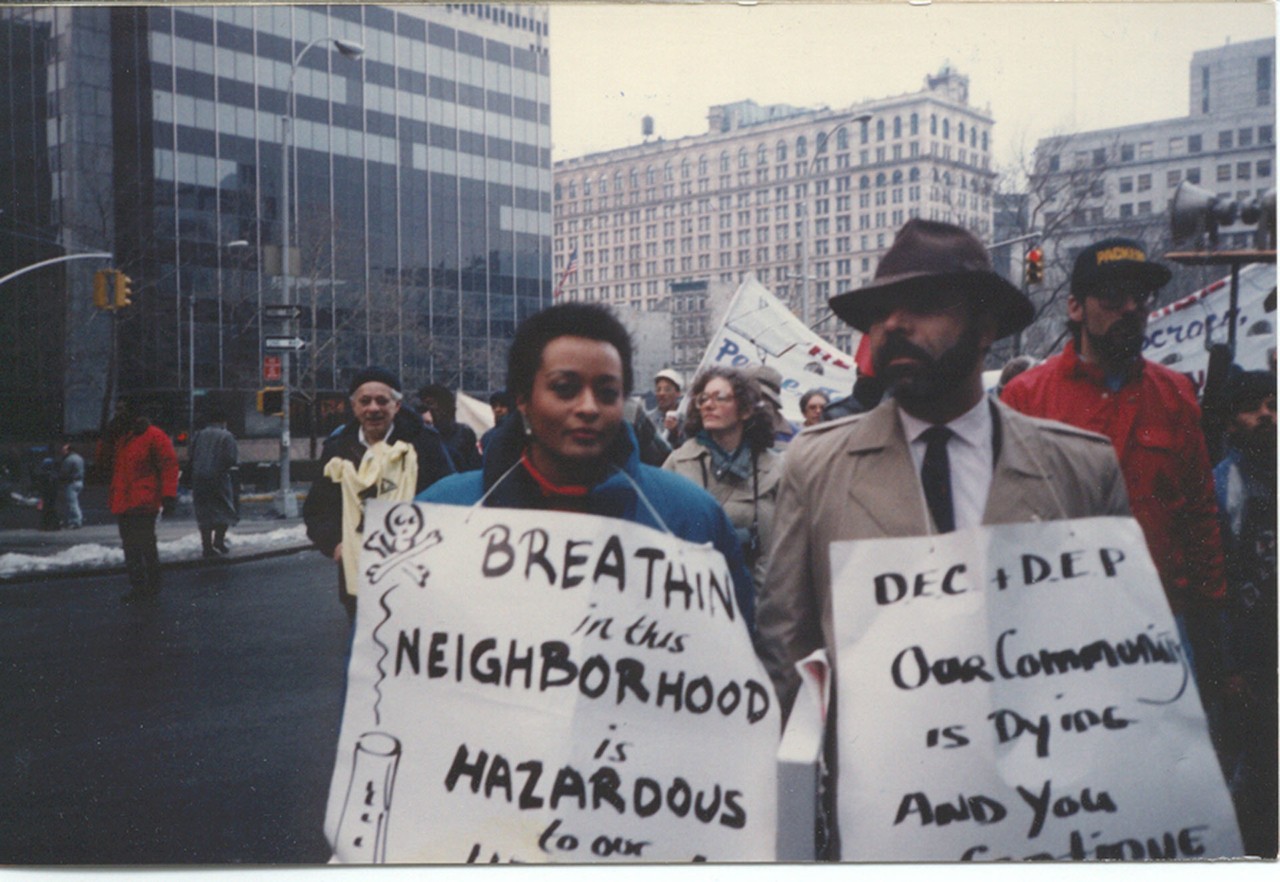

WE ACT co-Founders Peggy Shepard and the late Chuck Sutton raising awareness about poor air quality in Northern Manhattan. (Courtesy of WE ACT)

WE ACT co-Founders Peggy Shepard and the late Chuck Sutton raising awareness about poor air quality in Northern Manhattan. (Courtesy of WE ACT)

WE ACT continues to use a mix of activism, advocacy, and action in organizing against environmental racism, which for many years was not part of the discourse of the largely white and middle-class environmental movement. The organization works to ensure that low- income communities and communities of color can participate in the creation of fair and meaningful environmental policies that safeguard their neighborhoods and public health.

“Let’s not repeat the tragedy of COVID-19 with the climate crisis. Our city needs its essential workers, the folks who live in places like East Harlem. We cannot afford to watch them wither under heatwaves or be pushed out by gentrification. New York City must invest in these long-neglected, once-redlined communities, to make them more environmentally and economically sustainable. We can no longer let race, economic status or zip codes determine who lives and who dies in our city.”

– Peggy Shepard, We Act for Environmental Justice_

Sources

- “2019 NYC Citywide Evictions” by OpenStreetMap contributors.

- “Asthma” by Columbia Center for Children’s Environmental Health.

- “Bronx, New York, Report Card on State of the Air” by the American Lung Association.

- “CERO: Our Beginnings” by Cooperative Energy, Recycling, and Organics.

- “New York City Community Health Profiles by Borough” by the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.

- “NY lawmakers want Cross Bronx Expressway to be part of infrastructure plan” by WABC.