Session #7: Displacement in Harlem & Columbia Expansion (7/16/21)

Summary:

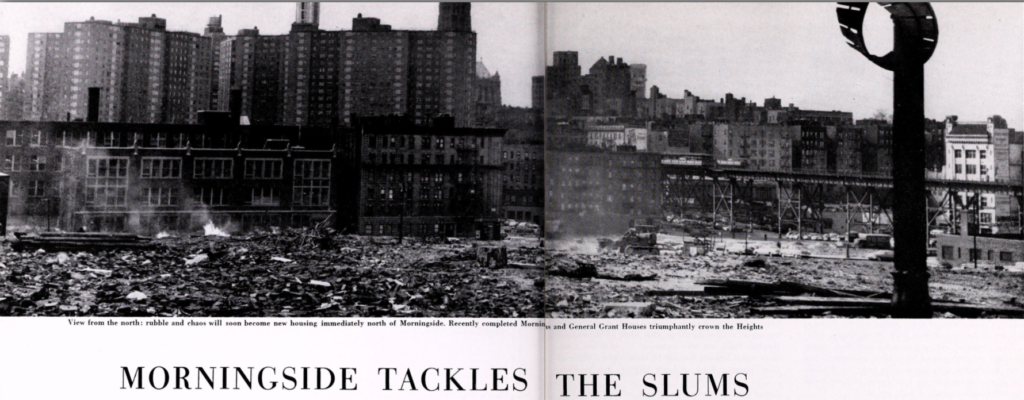

Since relocating from midtown Manhattan to the current locations in Morningside Heights in 1897, Barnard and Columbia administrations have sought to obtain real estate. In a study completed in 2018, the Trustees of Columbia University were identified as the second largest private landowner in New York City by number of buildings and parcels owned and the seventh largest private landowner by square footage. While Barnard owns nowhere near the volume or number of properties that Columbia does, the two institutions have used similar and sometimes coordinated tactics to marshall both the funding and the political will required for property acquisition and tenant eviction: declarations of blight and crime in Black and brown neighborhoods, slum clearance and urban renewal funding, and in the case of Columbia, eminent domain and the assertion of the private university as a public good.

We’ll look today at historical context for two moments in the expansion of the University and its affiliates: the formation of Morningside Heights, Inc. by Columbia, Barnard, and 12 other area institutions to support real estate development and institutional expansion using slum clearance and urban renewal funding in the 1950s and 1960s; and Columbia’s use of eminent domain and other approaches to its 2000s-present Manhattanville expansion. We’ll also look at the efforts of tenants and students to resist displacement, gentrification, and policing.

Presenter Bios

Martha Tenney is the Director of the Barnard Archives and Special Collections.

Brianna Sturkey is a Chicago native and alumna of Barnard College. She graduated Cum Laude with a bachelor’s degree in sociology and human rights. Brianna is currently employed as a litigation paralegal for Cravath Swaine & Moore and hopes to attend law school in the near future. During her time at Barnard, she took a keen interest in issues related to gentrification and housing displacement. Working with members of Community Board No. 9 – a West Harlem board comprised of residents, activists, and volunteers – she wrote a senior thesis that amplified the voices of local community members, which had been historically ignored by Columbia University. Brianna went viral last summer on Twitter and Instagram after sharing her thesis, gaining over 30,000 likes and shares. She has continued to address the issue of gentrification in Harlem by mobilizing student-led collectives and concerned alumni. Furthermore, she recognizes the issue of affordable housing is a national crisis and is currently volunteering with the Lugenia Burns Hope Center in Chicago to push forward a housing bill that would lift the ban on rent control in Illinois.

Michael Palma Mir — A lifelong and a second-generation resident of Hamilton Heights, Harlem, Mr. Palma has been a community activist all his adult life. Mr. Palma divides his time between work in the theater and photography as well as being an advocate for a better quality of life in West Harlem. Mr. Palma has twice graduated from Columbia University with a BA in English and a Master of Fine Arts from the Hammerstein II Center. As a photographer, Mr. Palma has documented cultural life in Upper Manhattan since the 1980’s and has curated and participated in various Upper Manhattan photo groups. Most notably, he co-curated and participated in “Vague Terrain: Manhattanville” at the Compton-Goethals Hall Art Gallery in City College, where Mr. Palma spent a year chronicling the architecture, artifacts, and people of Manhattanville; a photographic testimonial during a period of ongoing and dramatic changes for the community. More recently he curated a photo exhibit named “The Plumage of Another” for En Foco’s Apartment Gallery Series, and “Selfless Selfies” at the Northern Manhattan Arts Alliance Gallery, a black & white exhibit by Upper Manhattan photographers, narrating stories about their changing communities. Mr. Palma also conducts free photography workshops for the Fort Tryon Conservancy and for the Montefiore Park Neighborhood Association and is the resident staff photographer to the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum of Art and Storytelling.

As a community activist, Mr. Palma has focused on increasing West Harlem’s quality of life and affordable housing. Along with many other community volunteers, Mr. Palma is one of the volunteer leaders of the Montefiore Park Neighborhood Association, who seek to revitalize Hamilton Heights, by transforming Montefiore Park into a focal point of community life. MPNA activities is held at the park throughout the year, engaging residents of all ages, as well as enlist the collaboration of local schools, businesses, and city agencies. Reaching beyond the footprint of Montefiore Park, MPNA activities impact the surrounding Hamilton Heights neighborhood bounded by 133rd Street and 141st Street, St. Nicholas Avenue and 12th Avenue.

Mr. Palma is one of the founding members of the HDFC Coalition, which began in 1992 as an effort to advocate for improvements in the policies of the City of New York towards HDFC cooperatives. In early 2016, the Coalition decided to become more active in response to recent City efforts to terminate existing tax relief programs for HDFCs and modify regulations pertaining to HDFC buildings. In 2011, Mr. Palma joined Broadway Housing Communities as its Director of Housing and saw to the marketing and rent-up of its new affordable housing building on Sugar Hill. An active member of community board 9 Manhattan for the past 17 years, he has served on both the Housing and Arts & Culture Committees. In theatre, Mr. Palma produced and presented Spanish language classic and contemporary dramas for the Puerto Rican Traveling Theatre, INTAR and TeatroStageFest, and is currently the Executive Director of Teatro Círculo.

Guiding questions:

- How does the history of Columbia University expansion fit into the broader contexts of redlining, disinvestment, real estate speculation, and displacement?

- How has the University obscured and exploited the social dynamics of “blight” and the University-as-public-good to justify eminent domain over the years, and to this day? What are the implications of seeing Columbia as an extension of the State apparatus, as argued in Brianna Sturkey’s thesis?

- Narratives about Columbia as a whole often exclude the gendered specificities of Barnard politics. We can see these dynamics at play with the story of Linda LeClair in Maya Garfinkel’s essay. How do you understand gendered and racialized notions of safety, control, and autonomy as they relate to Barnard housing, then and now?

- What demands (regarding anti-gentrification, anti-expansion, tenant rights, etc.) have been made of the University and related institutions over time? How have the terms of negotiation shifted over time? What demands and tactics have been successful?

- Where do we go from here? Given the various forms of harm we have discussed, what reparative approaches can the university take?

Readings:

Pages 8-20, “Chapter 1: The Betrayal of the Liberal Assumptions of Urban Renewal” from Chronopoulos, Themis. Spatial Regulation in New York City: From Urban Renewal to Zero Tolerance. Routledge Advances in Geography 4. New York: Routledge, 2011. CLIO link / direct link to PDF

Garfinkel, Maya. “Rooming at Barnard,” April 2, 2020.

Minutes 23:55 – 35:20 from Sturkey, Brianna. Teach-in on Columbia University’s Gentrification of Harlem, MAD Columbia.

Mobilized African Diaspora (MAD) Demand Letter, August 31, 2020.

Minutes 27:20 – 36:30 from WNYC. “‘We Asked the City for Help and We Got a Raid’ | The Brian Lehrer Show.”

Recommended additional readings:

Coalition Against Gentrification: Raising Consciousness about Columbia’s Impact on the Surrounding Community, 2014

Student Coalition on Expansion and Gentrification, 2009-2011

Sturkey, Brianna. “The Ascension of Universities as Anchor Institutions and the Threat of Gentrification: Evaluating Columbia University’s Manhattanville Project.” Barnard College, 2020.

Baldwin, Davarian L. In the Shadow of the Ivory Tower: How Universities Are Plundering Our Cities. New York, NY: Bold Type Books, 2021, Chapter 3, pages 87-108.

Phillips, Tom. Saving the Blennerhasset, an Oral History of 507 West 111 Street in Morningside Heights, with Don Colflesh, Demi McGuire, Arthur Weinstein, George Gabriel, Wendell Dorris, Nellie Bailey, Paul Niemi, Deland Rivera, 2017.

Community Board 9 Manhattan 197-a Plan: Hamilton Heights, Manhattanville, Morningside Heights (with multiple revisions).

“West Philadelphia Collaborative History, Federal- and State-Funded Urban Renewal at the University of Pennsylvania.” Accessed June 9, 2021.

Session #6: Anti-Eviction Mapping Project—Collaboration and Care in Mapping Displacement (3/26/21)

Summary

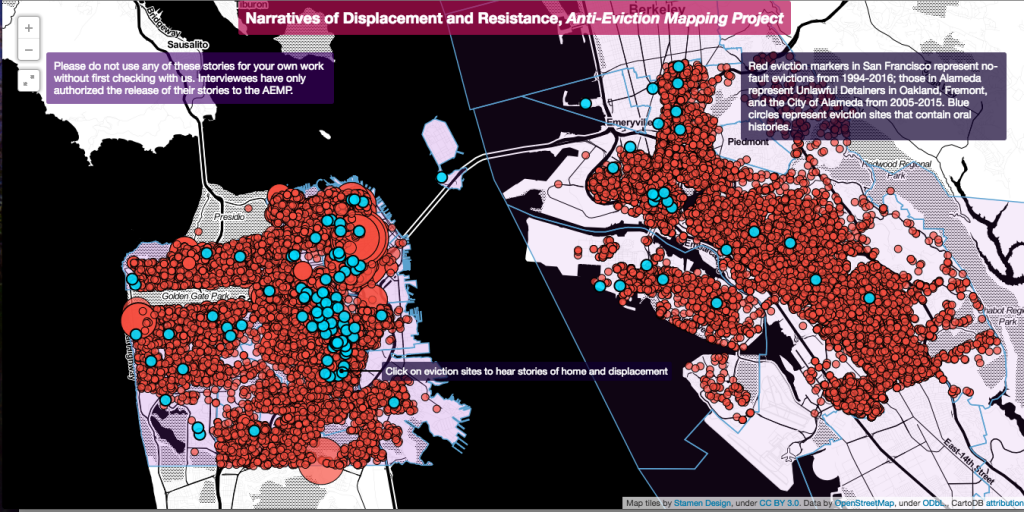

Founded in 2013 around a table at the San Francisco Tenants Union, the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project was formed among community activists with the intention of documenting evictions and tech-led speculative displacement in San Francisco. Now with chapters in Los Angeles, New York City, and the Bay Area, the project uses a variety of modalities that employ technology and storytelling to build tenant power in anti-gentrification fights. AEMP embraces a connected approach to housing, data, and cartographic justice that foregrounds mutual aid, embeddedness, and accountability.

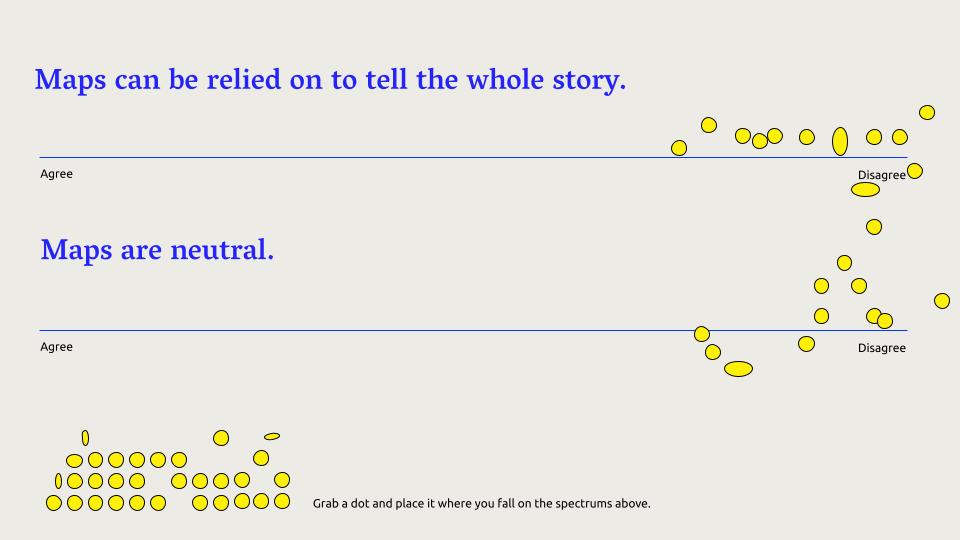

In this session facilitated by two long-time members of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project, participants explored the use of media and technology to liberate narratives of displacement, dispossession and resistance from forces that flatten them. Mainstream digital media traps the lives and stories of displaced folks in statistics, numbers in a chart, dots on a map— all masquerading as the “empirical truth.” During this session, we discussed media and research practices that complicate the totalizing forces of maps as well as leverage them as tools to reveal hidden histories, build community power, and give form to landscapes of injustice.

Presenter Bios

Ariana Faye Allensworth is a visual artist and researcher based in Brooklyn, NY. Her work builds upon interests in photography, spatial justice, and the politics of the archive. She has over 10 years of experience as a cultural producer and arts administrator, specializing in arts education and social impact strategy. She currently works as a Senior Designer at IDEO and has previously held positions at The International Center of Photography, The Center for Cultural Power, Youth Speaks, and Cultural Engagement Lab. Ariana is a founding member of the New York City chapter of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project.

Terra Graziani is a researcher and organizer based in Los Angeles, CA. Her work focuses on the dispossession and resistance of tenants in California cities and how policing and state violence are used to control people’s relationship to land. She founded and helps run the Los Angeles chapter of the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project and is Researcher at The Institute on Inequality and Democracy at UCLA.

Readings

- Tensions and Lessons from the Anti-Eviction Mapping Project by Terra Graziani and Mary Shi (with a focus on pages 7-14, folks are encouraged to read the full article)

- https://artwashing.antievictionmap.com/

- https://www.worstevictorsnyc.org/map

- https://shelterforce.org/2018/08/22/eviction-lab-misses-the-mark/

- Residual Black Data by Romi Morrison, (Folks are encouraged to listen to the full lecture, we’ll be focusing on the content covered from 09:15-21:25) https://vimeo.com/354276852

Reading/Discussion Prompts

- Romi invites listeners to consider, “What are we making inherently unknowable by making the world more measurable, familiar, and predictable?” In your experience, what are examples of ways of knowing the world that, in Romi’s words, “are discounted because of their inability to be neatly measured or efficiently accounted for”?

- During their lecture, Romi invokes the research of Rob Nixon who coined the term “slow violence” to describe the attritional impacts of oppressive forces on communities. In what ways do or don’t the maps and creative projects explored in the readings give visibility to slow violence?

- How might the mapping practices explored in the readings be stretching or pushing up against the traditional rules of cartographic design and/or knowledge production?

- What present day legacies do you see of redlining in the Worst Evictors and Art Washing map? As we think through redlining as a process, how can we also name the current day practices of real estate that have a similar impact/enact racial violence?

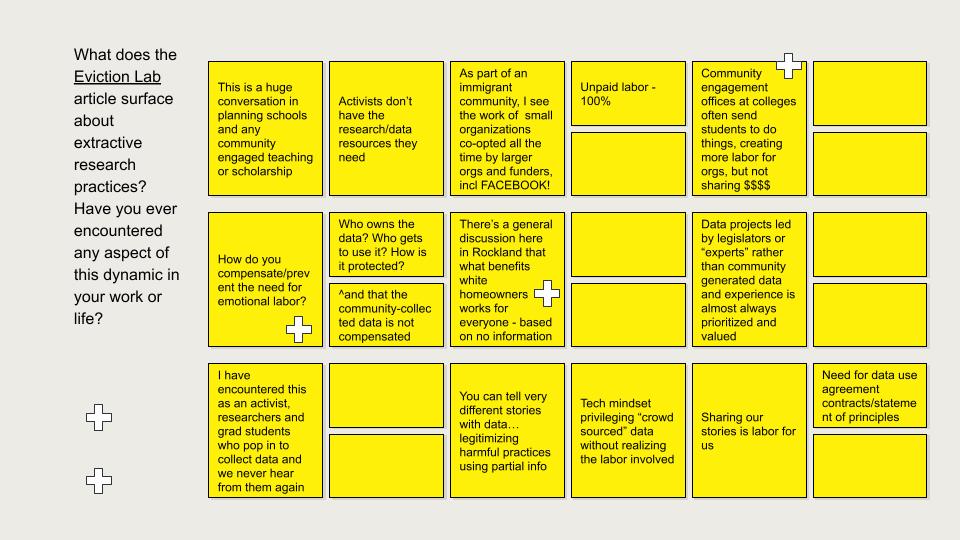

- What does the Eviction Lab article surface about extractive research practices? Have you ever encountered any aspect of this dynamic in your work or life?

Session #5: Gregory Jost – Undesigning the Extractive Economy (2/19/21)

Investing in a restorative infrastructure for community ownership and control

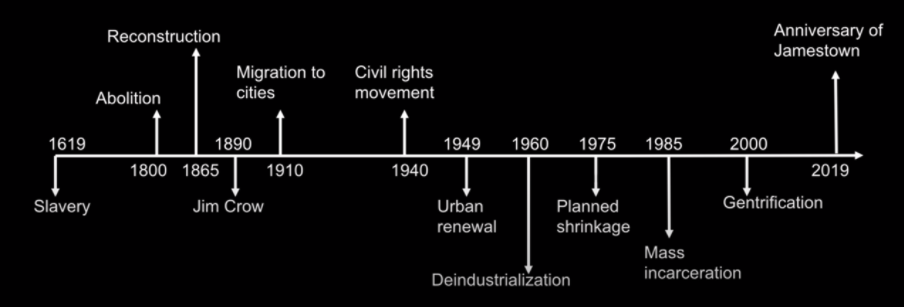

Redlining codified and structuralized explicitly racist sentiments and practices, embedding them onto maps that incentivized hyper-segregation and expanded the racialized extractive economy from a Southern Jim Crow focus onto the growing urban and suburban housing landscape in metropolitan areas across the country. Like Jim Crow, racial hyper-segregation served as a “lubricant of oppression,” as Craig Wilder writes in A Covenant With Color, setting a “foundation for a broader social agenda that put the black population at the mercy of their white co-citizens.” The economic prosperity of white communities in the post-WWII era was predicated on their racially restrictive nature, and thus on the disinvestment and devaluation of neighborhoods where Black folks and other people of color lived, undermining their cultural and economic vitality. Over time and through a series of devastating policies (e.g., Urban Renewal) and political philosophies (e.g., Benign Neglect), redlined areas were designed to become the so-called “deserts” for quality jobs, schools, food, financial services, social fabric, and other amenities and opportunities that we still experience today. The housing, education, food, criminal justice, health and financial systems all extract wealth and power from our communities, perpetuating the massive racial wealth gap, leaving us more susceptible to the consequences of a global pandemic and other coming crises.

Despite this sabotage, people have always been fighting back against the racist extractive economy, winning legislative battles such as the 1968 Fair Housing Act, the 1975 Home Mortgage Disclosure Act, and the 1977 Community Reinvestment Act. Communities of color have also turned to “fight forward” strategies such as self-help, mutual aid, anti-racist cooperatives, and community ownership. As we enter the third decade of the 21st Century, a growing movement of fight forward strategies and coalitions grounded in racial, gender and climate justice are making headway in grassroots, municipal and statewide initiatives. Coupled with a growing understanding of how structural racism permeates our nation’s history and the stories of resistance movements going back centuries, the opportunity for a comprehensive reframing provides us with hope for “undesigning” the racist extractive economy. In communities of color across New York City and State, groups are fighting concertedly for community ownership of land, investment in cooperative economics, for self determination and economic democracy. A very recent campaign focuses on the creation of public banks that can hold municipal deposits to invest in this infrastructure. Similar movements are happening in other states, and the events of 2020 have added even more urgency to our work. Our conversation will build off of the last session led by April de Simone and lead us forward into the makings of an alternative future.

Group portrait of men and women outside the Provident Home Beneficial Society of Pennsylvania, Richard A. Cooper, president, 2315 Wylie Avenue, Hill District

© Carnegie Museum of Art, Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive

Gregory Jost is a Bronx-based scholar and organizer embedded in grassroots communities working for economic self-determination. He holds extensive experience and expertise in the convergence of community organizing, grassroots research and data visualization, affordable housing, the history of race and place in American cities, and strategies for community control of reinvestment. Jost is an Adjunct Professor of Sociology and a member of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion Council at Fordham University. As a Policy and Campaigns Advisor for Banana Kelly Community Improvement Association in the South Bronx, he is deeply involved in coalition work fighting back against predatory equity and displacement, and fighting forward for community ownership and economic democracy. Gregory also serves as the Board Chair of New Economy Project and is currently writing a book on the Bronx’s history fighting against redlining. Previously he helped launch the Undesign the Redline work of Designing the WE.

Reading/Viewing

– Wilder, Craig Steven. c2000. A Covenant with Color Race and Social Power in Brooklyn /. The Columbia History of Urban Life. New York : Columbia University Press. (Chapter Nine)

– “Co-Op City.” 2019. Urban Omnibus. May 2, 2019.

– Films, Kontent. 2014. How We Live: A Journey Towards a Just Transition (7 mins 21)

– 2013. CERO: Our Beginnings. (3 mins 50)

Reflection Questions / Prompts

– It is critical that our nation’s history of racist disinvestment and community reinvestment be part of this movement.

– How do we learn from our past and not repeat systemic mistakes, even with good intentions?

– How do we focus on core issues of power, profit and process to chart a new path forward?

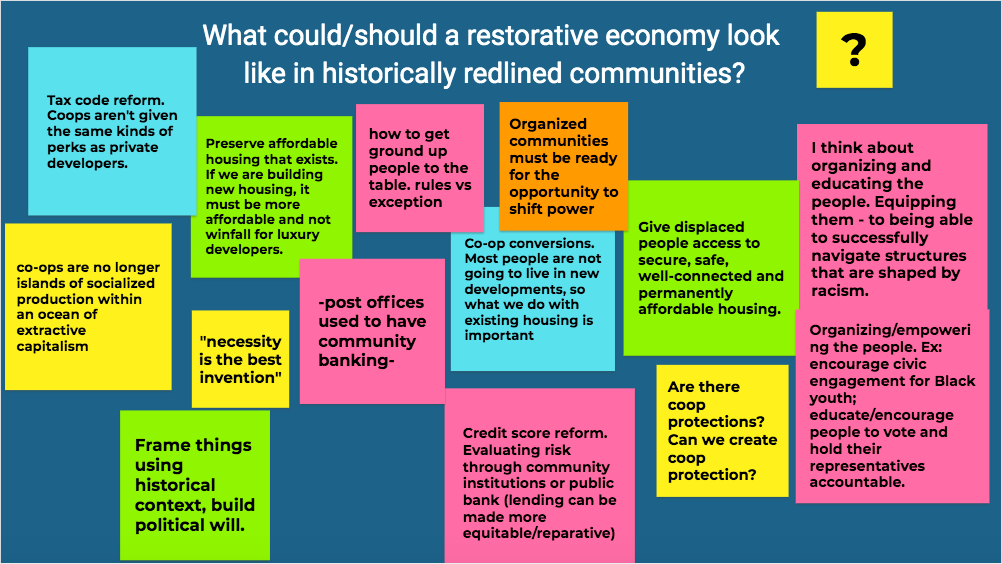

– What would a new and just economy look like in historically redlined communities?

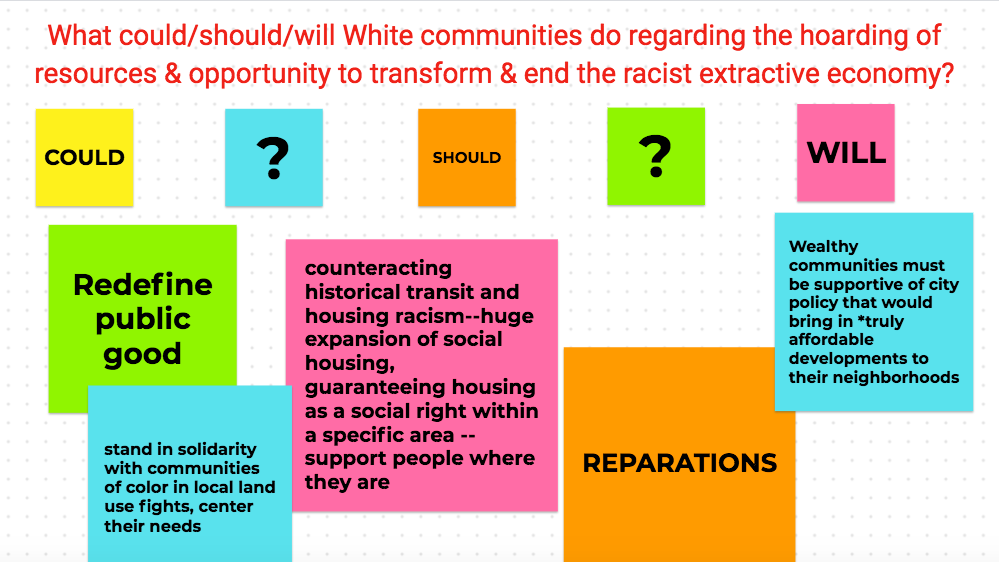

– What has to happen in white communities regarding the hoarding of top quality resources and opportunity to end the racist extractive economy?

Session #4: April DeSimone – Inequity and Exclusion by Design (1/22/21)

In the 1960’s, sociologist John McKnight applied the term redlining to denote a pattern exercised by realtors, banks, insurance companies, government agencies, and others demarcating areas in red deemed to be “undesirable.” This practice in both the private sector and government on multiple levels would reinforce a mental branding of undesirability associated with the very racial and ethnic makeup of such communities, among other factors. These collective policies, practices, and investments had long been used as strategies to reinforce residential segregation, solidifying hierarchical perceptions of human value along racial, spatial, and class lines. ‘Redlined’ communities not only were marginalized but intentionally disinvested.

The rapid scale of redlining practice would be adopted and incorporated into New Deal programs like the Home Owners Loan Corporation and the Federal Housing Administration. Federal policies under both these agencies and others, aided and abetted private industry to mobilize massive public investments into infrastructure projects, job creation, financial institutions, and many other industries, creating significant opportunities for countless households across this country; particularly wealth-building capacities due to home ownership. Essentially, these policies created the American Middle Class. As history has shown, many Americans benefited from newly found gains in home ownership, and enhanced public programs like education. While such policies benefited many, history has also shown that public and private stakeholders worked to simultaneously ensure those deemed “undesirable” would never have the same access to those benefits, especially Black and Brown communities.

Private industries, with the support of government policies and investments, entrenched structural inequity along racial and class lines into the design of cities and beyond. This spatialized psychology shifted segregation from visible superstructure to ubiquitous infrastructure: further isolating communities even while ‘colored only’ signs came down. Soon without access to banking, insurance or even healthcare, marginalized groups confined to “undesirable” neighborhoods were forced on a path of “urban decay,” accelerated by subsequent countless other programs like Urban Renewal, Slum Clearance, and Broken Windows. By many means, this American geography became a machine for reproducing a society divided by race and class. Investment drained from concentrated ‘inner city’ zones of poverty, mostly comprised of people of color, while investment poured into the rapidly expanding wealthier, whiter neighborhoods. This type of structural, geographic design alters what is possible in the decades that follow.

We still need to “undesign” the impacts of such policies. Today, even when money flows back into once-Redlined zones, the tide of investment cannot raise all boats. It washes people away. Broad wealth building still does not reach those of us who have been historically devalued. Instead, we are faced with a legacy of lingering bias, living with the scarlet letter of racialized policies, practices, and investments, and its cross-generational effects on wealth, income, well being and ownership. In this session, Undesign the Redline creator April DeSimone describes how projects by her social justice design firm designing the WE offer tools to “undesign” the metaphorical redline that perpetuates perceptions of ‘deserving; and ‘undeserving’ according to race, place, and class.

April De Simone has over 15 years of experience in strategically designing, developing and launching for-profit, non-profit and government projects.Continuing to advocate for social innovation, Ms. De Simone is co-creator of various for-purpose ventures and initiatives that promote market based solutions to address complex social challenges. A Dean Merit Scholar, she recently completed her Master of Science in Design and Urban Ecologies from Parsons School for Design. Ms. De Simone continues to be recognized for her leadership and dedication in supporting frameworks that promote a just and equitable society.

Readings

– Robinson, Nathan J. 2016. “It Didn’t Pay Off.” Jacobin Magazine, October 1, 2016.

– Walker, Richard. 2019. “The New Deal Didn’t Create Segregation.” Jacobin Magazine, June 18, 2019.

Media

– NYC Department of Health. 2018. Undesign the Redline. (4 min 32 sec)

– Ayers, Hannah, and – Lance Warren. 2010. That World Is Gone. (approx 20 min.)

Housing Stories (12/18/20)

Session #3: Neighborhood Battles in NYC: the Politics of Zoning with Naomi Schiller and Vanessa Thill (11/19/20)

Gentrification in NYC has been lamented as inevitable, partially applauded as ‘progress,’ or blamed on artists and young people. In this session, we will debunk common notions about gentrification by examining the real causes of these urban transformations that systemically displace low income communities of color. We will consider the tools used by the city government and private developers to create these changes (for instance: financial instruments such as geobribing and tax breaks, and manufactured public consent in the land use process). Our case study will be Two Bridges in Lower Manhattan, but we will take a brief look at neighborhood rezonings across the city to see how people on the ground are fighting back, not only to block luxury towers, but also to advocate for their own community-led vision of the city.

Naomi Schiller is associate professor of anthropology. Dr. Schiller’s research and teaching focus on urban politics, climate justice, ethnographic film, and the state in Latin America and the United States. Her new research explores community activism, social class, coastal adaptation, and environmental justice in New York City.

Vanessa Thill is the Exhibits Designer at Barnard’s Milstein Center. She is an artist and writer who graduated from Barnard in 2013. She works as an organizer with Art Against Displacement and the Coalition to Protect Chinatown and the Lower East Side. She is involved in housing justice and anti-displacement work in several capacities.

Reading

– Chapter 2: Planning Gentrification, Capital City: Gentrification and the Real Estate State by Samuel Stein. Verso, 2019. (25 pages)

– Six Down, One to Go: Where de Blasio’s Rezonings Stand, by Sadef Ali Kully, Sep. 2020.

Suggested Reading:

– Fighting the Megatowers: A Tale of Two Bridges Op-Ed by Alessandra Ametrano, Steph Kranes, Vanessa Thill, Left Voice. October 23, 2020

– The People vs. Big Development By Stefanos Chen, New York Times. Feb. 7, 2020

– “It’s Never Over” Photo Essay By Yana Kunichoff , Kelly Viselman, Jewish Currents, Oct. 2020

– A Green New Deal for Housing by Daniel Aldana Cohen. Jacobin, Feb. 2019

Prompts

– To what extent should we understand gentrification as a result of individual choices and to what extent is this process a product of large-scale forces including governments and private capital?

– What forces in the second half of the twentieth century led to gentrification in the US

– Consider the “economics of gentrification” versus the “politics of gentrification.”

– What outcomes have you experienced from the process of gentrification in your neighborhood or in surrounding NYC neighborhoods?

– How is gentrification typically justified, according to Stein?

– What other ways might we generate revenue besides property taxes? Why does the City prefer property taxes over other solutions?

– What change do we want and need in our neighborhoods and communities?

Session #2, Hot Cities: Redlining and Environmental Injustice with Logan Brenner and Elizabeth Cook, Barnard Environmental Studies (10/30/20)

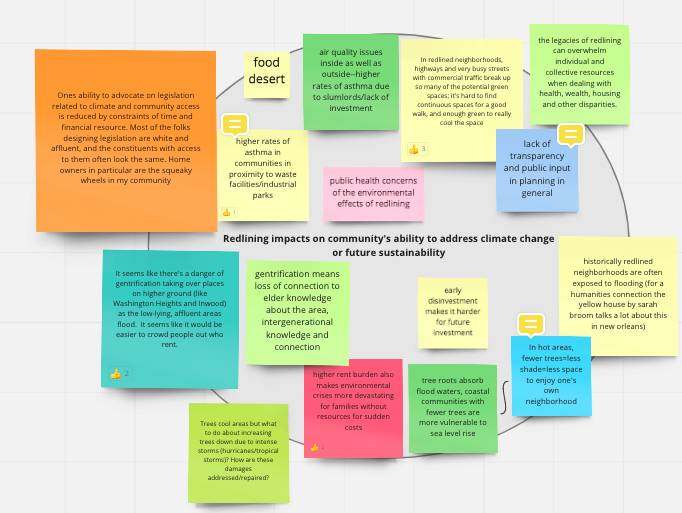

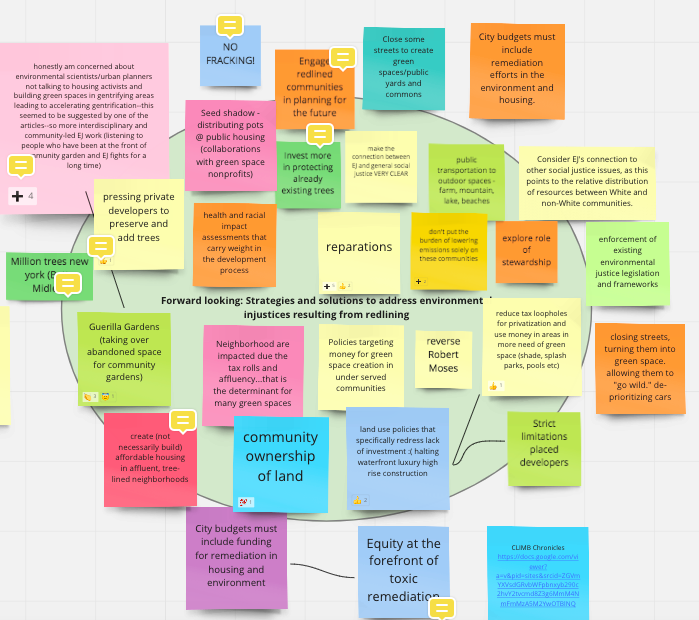

In this session, we discussed the ways in which discriminatory housing practices have led to various inequities in how people access and interact with the environment. This manifests as public health crises (e.g. increased rates of asthma), exposure and increased vulnerability to climate change and extreme events (e.g. extreme heat waves), and being physically, emotionally, or intellectually denied access to different ecosystems.

Elizabeth Cook is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Science. She is an urban ecosystem ecologist. She works collaboratively with interdisciplinary scientists and local practitioners through participatory methods to envision positive futures addressing urban sustainability, resilience, and climate justice. She teaches Environmental Data Analysis and co-teaches Senior Seminar in Environmental Science with the senior thesis students. She earned a BA from Wellesley College and a PhD from Arizona State University.

Logan Brenner is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Environmental Science. She is a paleoclimatologist (study of past climate) and specifically studies the geochemical composition of coral skeletons to reconstruct past oceanic conditions in the tropics. She is currently teaching the Workshop in Sustainable Development and co-teaching the Senior Seminar in Environmental Science with the senior thesis students. She earned a BA in Geosciences from Skidmore College and PhD in Earth and Environmental Science from Columbia University.

This program was funded in part by Humanities New York with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities.

Listening:

– Anderson & McCinn Sept 2019 (8 minute listen + good visuals & background information) NPR As Rising Heat Bakes U.S. Cities, The Poor Often Feel It Most

– Anderson Jan 2020 (3 minute listen) NPR: Racist Housing Practices From The 1930s Linked To Hotter Neighborhoods Today

Reading (Popular/Non-Academic Article)

– Plumer & Popovich Aug 2020 NYT (interactive feature article): How Decades of Racist Housing Policy Left Neighborhoods Sweltering

Reading (Academic Articles)

– Namin S, Xu W, Zhou Y, Beyer K (2020) The legacy of the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation and the political ecology of urban trees and air pollution in the United States. Soc Sci Med 246(). doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2019.112758.

– Hoffman JS, Shandas V, Pendleton N (2020) The effects of historical housing policies on resident exposure to intra-urban heat: A study of 108 US urban areas. Climate 8(1):12.

Additional readings:

– Krieger N, et al. (2020) Structural racism, historical redlining, and risk of preterm birth in New York City, 2013- 2017. Am J Public Health 110(7):2013–2017.

– Grove M. et al (2018). The Legacy Effect: Understanding How Segregation and Environmental Injustice Unfold over Time in Baltimore. Annals of the American Association of Geographers, 108(2) 2018, pp. 524–537

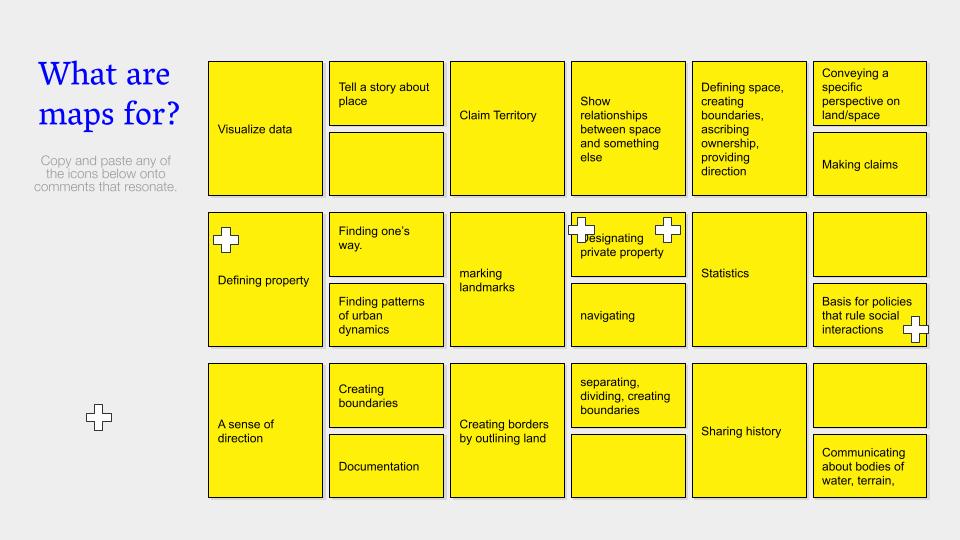

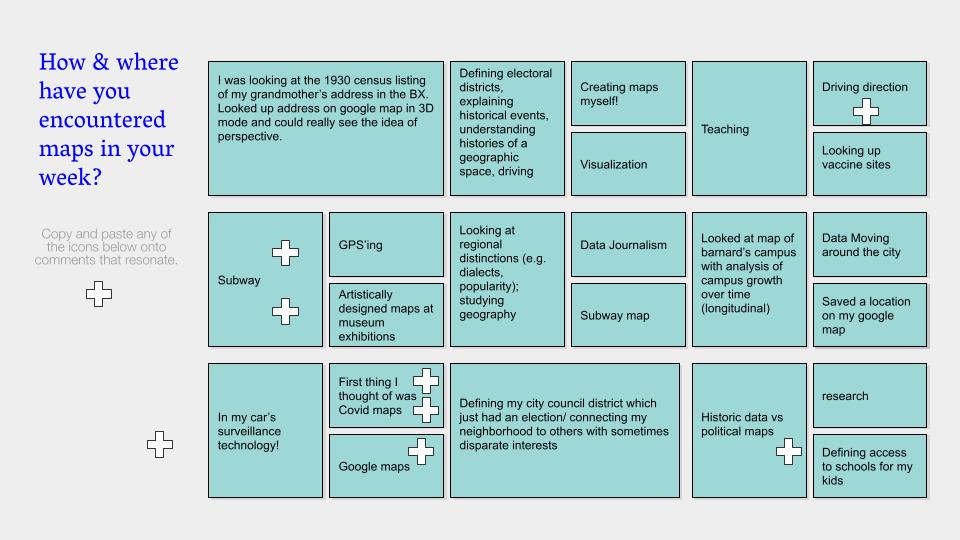

Idea maps generated during the workshop:

Housing Stories (10/16/20)

- Intentions of session

- Parsing our relationship to different housing-related policies

- Free space to reflect

- Living with and working through contradiction

- Conversation guidelines

- Assume best intentions

- Mute when you’re not speaking

- Honor each other’s speaking

- Suspend judgement

- Key Words

- Secure

- In transit

- Lucky

- Caretaker

- Insecure

Closing inspiration: Kansas City Tenants take action against evictions

Session #1, Changing the Narrative: A Public Housing Project with Pamela Phillips (9/24/20)

The dominant narrative related to the public housing program is centered around the consequences of chronic disinvestment and “concentrated poverty” – crumbling infrastructure, toxic living conditions, and crime and drug-ridden neighborhoods. Consequently, this destructive narrative has influenced policy responses that led to discriminatory practices, over-policing, community surveillance, displacement and privatization. Residents’ voices have been mostly excluded from the discussion and decision-making process. Pam Phillips spoke with us about the Changing the Narrative project that she has researched and developed at BCRW. It is a resident-centered, place-based community engagement project whose mission is to alter the discussion around the public housing program and experience to be more inclusive of resident voices and experiences.

During our session we made space for personal accounts of housing and community. We talked about how access to education and healthcare are intertwined with housing, and how vital it is to have a safe home. We talked about what we love about our neighborhoods (like bodegas and community gardens). We also heard about experiences of being targeted by police and being pushed out of one’s home in public housing and in rent-stabilized units. We learned about the current crisis of privatization of NYCHA that threatens a crucial resource for low-income New Yorkers. (Justice for All Coalition just put out a demand letter seeking immediate repairs and public investment in NYCHA that you can sign here.) We thought through some of the impacts of the privatization of public housing: evictions, homelessness, consolidated real estate power, and corruption in electoral politics. From there, we thought about what a neighborhood would look like where racial hierarchy has been “undesigned”? Some ideas included returning to indigenous practices, co-ownership and community living, sharing food and childcare, cultivating open green space and vegetable gardens.

Pamela A. Phillips is Senior Program Assistant at BCRW and leader of the Poverty and Public Housing Working Group, which has produced the website, “Changing the Narrative: A Public Housing Project,” housing community stories and alternative understandings of public housing in New York City.

Readings:

– Housing Segregation and Redlining in America: A Short History | NPR, 2018. (6 min)

– Samuels, A. (September 22, 2015). The Power of Public Housing. The Atlantic.

– Ferré-Sadurní, L. (June 25, 2018). The Rise and Fall of New York Public Housing: An Oral History The New York Times.

– Rosenblith, G. G., & Rosenblith, G. (September 8, 2020). Perspective | Covid-19 has exposed the consequences of decades of bad public housing policy. Washington Post.

– Congressional Research Service. (February 13, 2014). Introduction to Public Housing. R41654. EveryCRSReport.com

– Rothstein, Richard. (December 17, 2012) Race and Public Housing. Economic Policy Institute.

– Goetz, Edward G. New Deal Ruins: Race, Economic Justice, and Public Housing Policy. Cornell University Press, 2013. (E-Book Access through Columbia Libraries – requires Columbia UNI)

Session #0, State-Sponsored Inequality and Redlining with Angela Simms and Mary Rocco (6/11/20)

The practice of “redlining” is one tool of exclusion and extraction widely used by governments (federal, state, and local), financial institutions (e.g., banks and insurance companies), and real estate agencies to withhold resources from Black communities in racially-segregated cities, while still realizing profits for White people and White-controlled institutions. These processes are cumulative and interdependent and evolve from the post-Reconstruction period forward (1877-to the present). And they are themselves legacies of the slave system and the attendant race and capitalism logics and practices established in the Colonial period.

Readings:

– Oliver and Shapiro, Black Wealth White Wealth: A New Perspective on Racial Inequality

– “A Secret Meeting in South Bend,” United States of Anxiety (podcast), WNYC

– William Darity, Jr. and Kirsten Mullen, The Inquirer Op-ed: “The racial disparities of coronavirus point yet again to the need for reparations”

– Documenting the Crossroads Photo Exhibit by Camillo Vergara, National Building Museum

– Timeline 1&2 for the 400 Years of Inequality project

Prompts

1) In what ways is the state “racialized”? What are the manifestations prior to the Modern Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s-1970s? What are the forms afterward? How are historical and contemporary forms connected?

(2) Why do you think Oliver and Shapiro choose the metaphor “sedimentation of inequality” to describe African Americans’ cumulative and mutually interdependent disadvantages? Why is wealth an apt measure of this phenomenon? What does wealth miss?

(3) Overall, what do today’s pieces tell us about the types of remedies needed to correct racial injustice and imagine more inclusive social systems?